Dr Andy Bowles takes a tour of the supermarket to show us why labelling is often misleading…

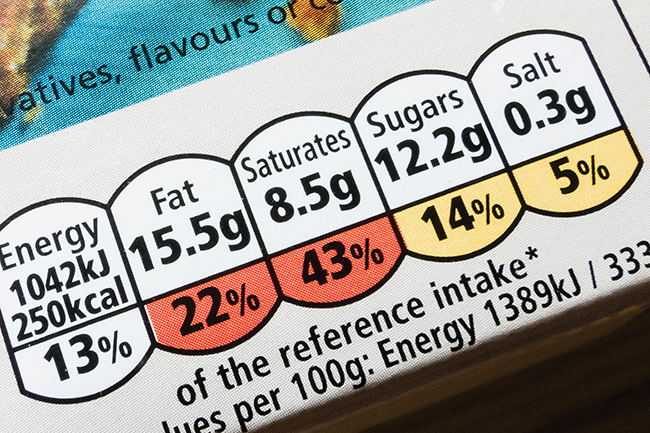

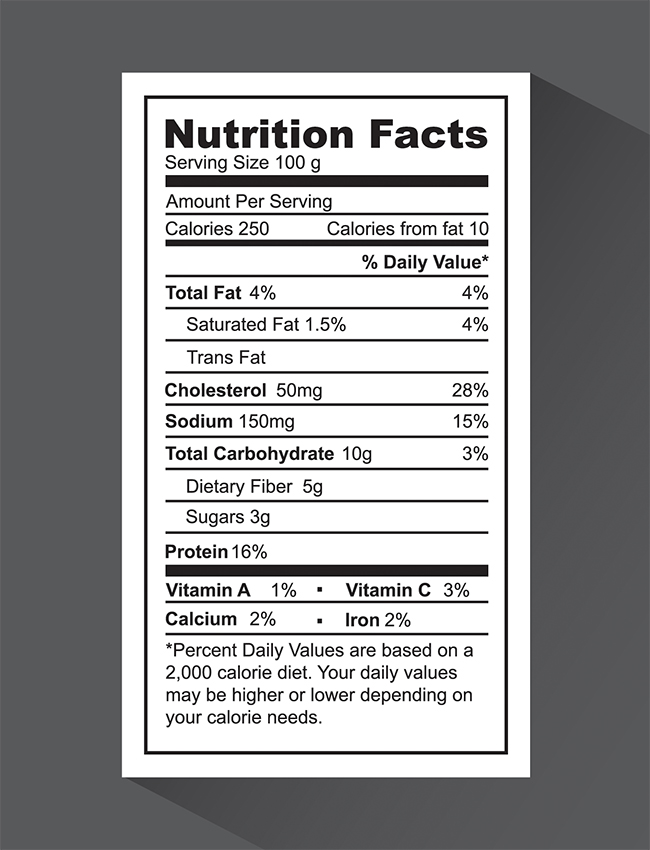

We all want to eat healthily and rely on the information provided on food labels to help us make the right choices. Since December 2016, most foods are required to include full nutritional information on the label, but how many of us have the patience to scrutinise this nutritional information before we put the product in our basket?

In practice most of us look for the ‘headlines’ in the form of claims on a food label and place our trust in the manufacturer to ensure that these statements are accurate. Common claims include ‘Low fat’, ‘Good for you’, ‘Healthy choice’ and so on. Unfortunately, some of the claims that we rely on are inaccurate, incomplete or downright misleading.

I raised this point with a journalist who asked me to prove what I was saying. I took her to one of the major high street retailers and within 15 minutes had filled a basket with obviously illegal foods. Some were making misleading claims, most were not providing enough information to justify the ‘headlines’ or to meet their legal obligations. The situation is worse in independent retailers and with artisan and regional foods. The internet is also becoming a ‘wild west’ of inaccurate claims, with many businesses not realising that the same rules apply to their websites, Twitter and Facebook postings as to their food labels.

To be fair, some manufacturers take their responsibilities to correctly inform the consumer very seriously, but their great work is undermined by others who show a disregard for the law. So, what are the rules and what are the issues?

Health claims

Health claims are ones that suggest there is a health benefit from eating a particular food – such claims can be either general or specific. General claims don’t make a clear statement on the benefits of eating a food, but instead use sweeping statements like ‘Good for you’ or ‘Healthy’. These are only allowed in law when a more specific health claim, which has been authorised by the European Commission, is permitted to be used on the label.

Specific health claims have been scientifically proven and can only be made on a label where it is also clearly stated how much of the food is required to obtain the claimed healthy effect, together with a statement indicating the importance of a varied and balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle. The label must also, where appropriate, give warnings about over consumption of the food and details of any person who should avoid the food.

For example, beta-glucans are naturally found in oats and have been scientifically proven to have some beneficial health effects. One authorised health claim which may appear on porridge oats is: “Beta-glucans contribute to the maintenance of normal blood cholesterol levels.”

However, the claim may be used only for food which contains at least 1g of beta-glucans from oats, oat bran, barley, barley bran, or from mixtures of these sources per quantified portion. In order to bear the claim, information must be given to the consumer that the beneficial effect is obtained with a daily intake of 3g of beta-glucans from oats, oat bran, barley, barley bran, or from mixtures of these beta-glucans.

Nutrition claims

Nutrition claims are those which refer to the beneficial nutritional properties of a food such as ‘Low fat’, ‘High protein’ or ‘Low in calories’. There is a list of permitted nutritional claims which can be used together with the rules that must be followed. For example, a typical nutritional claim refers to high levels of vitamins or minerals. A claim that a food is a ‘source’ of named vitamins or minerals can only be made if there is a significant amount of the named vitamin or mineral present in the food. In order to make a ‘High in vitamin or minerals’ claim, there must be twice the ‘significant amount in the food’.

For example: in most foods the ‘significant amount’ of Vitamin C set out in law is 12mg per 100g. If this amount is present in the food, the label can refer to “a source of Vitamin C” or words of a similar meaning. If there is at least 24mg per 100g, the food can claim that the food is “high in vitamin C”. If there is less than 12mg per 100g, no mention of Vitamin C can be made on the label.

Other claims

Some other claims are also subject to legal restrictions such as ‘gluten-free’, but most are not. The main criteria governing the use of most claims is that they are accurate, honest and substantiated. However, there are exceptions: for example, no food can claim to treat or cure a disease and any references to the treatment of cancer are prohibited.

The seven deadly sins of food labelling

‘Hang on a minute’, I hear you say, ‘there are lots of products on the supermarket shelves that claim to be good for me using phrases like ‘bursting with antioxidants’. Are they legal?’ The short answer is no – there is widespread non-compliance with law when it comes to food claims. Here’s a list of the most common failings:

1 Use of general health claims without including a specific, authorised claim

If you see terms like ‘healthy’ or ‘good for you’, look for a claim which refers to a specific ingredient, for example:

- “Calcium contributes to normal energy-yielding metabolism.’

- “Biotin contributes to the maintenance of normal skin.”

2 Use of non-approved health claims

The following are examples of claims that have not been scientifically substantiated and cannot be used on food labels:

- ‘Antioxidants protect cells from the harmful/damaging effects of free radicals. Antioxidants protect against oxidation, which causes cell damage. Contains antioxidants.’

- ‘Dietary fibre helps to reduce fat absorption.’

- ‘Wheat grain fibre helps with weight control.’

As a general rule, any claim which states a beneficial health effect of ‘antioxidants’ is unlawful and misleading.

3 Health & nutrition claims on unhealthy foods

Health and nutrition claims are intended to provide the consumer with accurate information regarding the benefits of eating particular foods. However, the presence of, for example, a vitamin in a high fat food does not make it healthy. We regularly advise clients on the reformulation of unhealthy foods to make them more healthy and allow them to use permitted claims. There are plenty of foods which are high in fat and/or sugar but which make misleading claims regarding the presence of vitamins and/or minerals.

4 Insufficient vitamins or minerals to make a valid claim

In order to make a valid claim about the presence of vitamins and/or minerals in a food there must be a legal minimum of the vitamin or mineral present. Terms like ‘bursting with vitamin C’ can only be made if there is sufficient vitamin to make a ‘high in’ claim.

5 Incorrect wording

Where a food is permitted to use an authorised health claim, they must use the correct wording and ensure that the consumer is reminded of the importance of a balanced and varied diet. Some labels ignore the approved wording, which makes it difficult for consumers to compare similar products.

6 Claims such as ‘natural’ which are not substantiated

The term ‘natural’ should not be used when the product contains refined ingredients, for example sugar.

7 Free-from

Such claims should only be made when similar products commonly include the ingredient referred to. For example ‘gluten-free’ should not be used on a product where this product would not usually contain gluten anyway. As such, a jar of strawberry jam should not be labelled gluten-free because all jams are indeed gluten-free. However a ‘gluten-free’ pasta alternative would be acceptable because most pasta is made from wheat and includes gluten.

About the author

Dr Andy Bowles is a Specialist Food Solicitor who runs the niche law firm ABC Food Law, who provide training on behalf of the Food Standards Agency to local authority food officers. ABC also run a food label assurance scheme ABC Legal Labels (www.abc-legal-labels.co.uk). As well as being a solicitor, Andy is a qualified microbiologist and Fellow of the Institute of Food Science and Technology.

Dr Andy Bowles is a Specialist Food Solicitor who runs the niche law firm ABC Food Law, who provide training on behalf of the Food Standards Agency to local authority food officers. ABC also run a food label assurance scheme ABC Legal Labels (www.abc-legal-labels.co.uk). As well as being a solicitor, Andy is a qualified microbiologist and Fellow of the Institute of Food Science and Technology.