The battle our body has fighting off allergens is a complex one. Dr Thomas Bohner reckons there is a more rational reason for the unwanted invaders to triumph…

A new definition of allergy

An allergy is the logical (not misguided!) response of our immune system to the intrusion of a foreign substance (allergen) through the previously damaged skin or mucosal barrier. Or, to state it somewhat more comprehensively: an allergy is the, usually, violent reaction of the immune system to a foreign substance that has managed to breach the outer barrier of the skin at tight junctions, that have been destroyed (e.g. by enzymes). The immune system then attempts to destroy this intruder by any means, a defence often accompanied by violent reactions such as watery eyes and a runny nose, asthmatic episodes or rashes.

Human skin cells are closely linked to each other to form, what is normally, an impenetrable barrier. This connection between two skin cells is composed of a barrier called tight junction which holds the cells together and allows for small substances to be released or taken in through the skin.

If these tight junctions are destroyed, particles such as parts of grass pollen, or other allergens, have unrestricted access into the body. As long as the components of the grass pollen cannot penetrate the skin, they remain harmless.

The skin is our largest and most important defensive organ. It is the first barrier of our immune system. There are two other barriers or ‘safety nets’ offered by our immune systems: the non-specific defence taken up against all intruders and the specific defence aimed, as the name suggests, at specific targets. Imagine the immune system as the fortifications of your domain, the body: the skin corresponds to the moat, after which the invaders need to conquer two massive defensive walls to penetrate into the interior.

A fortified castle is very difficult for attackers to take from the outside. They first have to swim across the moat and then climb over two very high walls. The defenders of the castle can usually ward off such attacks with ease. So what would crafty aggressors do?

They place a spy in the castle who then lowers the drawbridge from within, letting in their compatriots by the hordes. Once in, battle is waged between the attackers

and defenders.

How allergens pass through our skin

The same thing happens with our skin. Destruction of the tight junctions results in holes appearing in our body’s defensive system (the skin). These are, of course, not visible to the naked eye and are so small that no blood flows through them. They are only detectable at the molecular level, and only smaller molecules (e.g. enzymes) and smaller viruses can slip through them. In the same way, possible allergens can penetrate the skin and enter our bodies, triggering our immune system’s violent defence of its castle (our body) against the invading allergen(s).

The allergen, which is harmless outside our body, becomes a foreign body within, an intruder that must be destroyed by any means. An appropriately intense response from our immune system is then triggered. This is why the ideas of conventional medicine regarding our immune system’s overreaction, or misguided reaction, do not make sense. We are dealing with a foreign body that has already managed to overcome three immune defence systems and is now being fought against, with all due ferocity, by our immune system. Our immune system is behaving consistently with its previous lines of defence: there is no overreaction.

So how do scientists arrive at the notion that our immune system is overreacting? They refer to the high levels of immunoglobulin E (IgE) that coincide with allergies.

However, they are overlooking the fact that the increased IgE is caused by the destruction of the tight junctions. Certain enzymes (such as proteases) are capable of destroying these tight junctions and other regulatory mechanisms of the immune system, including the system that regulates the production of IgE, one of the key antibodies in the body’s war against allergens. If these regulatory mechanisms are destroyed, then IgE level automatically shoots up. Scientists conclude that our immune system has reacted excessively, while ignoring the cause for the higher IgE counts: the destruction of tight junctions and the IgE regulatory system.

The harmful role of killer enzymes

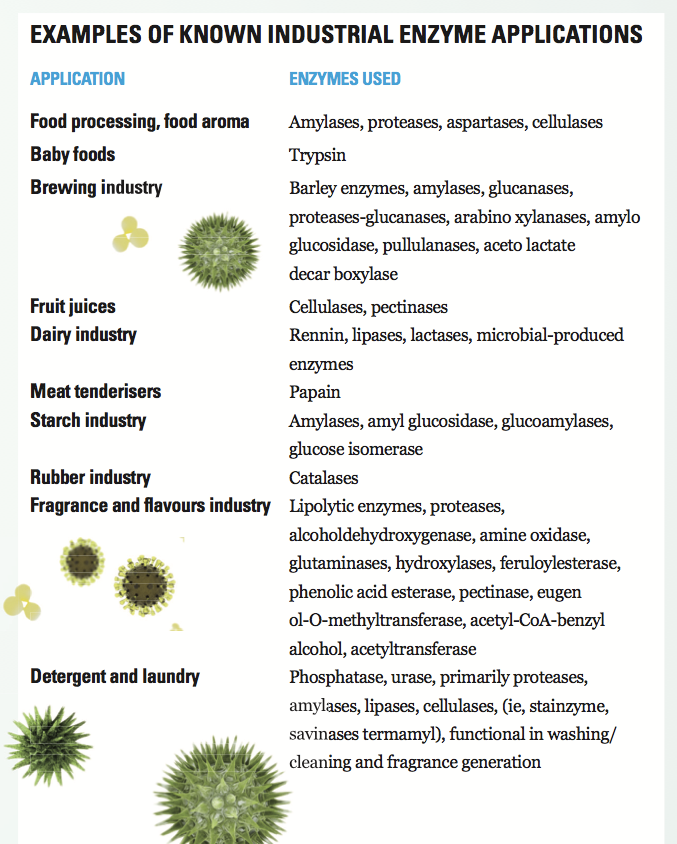

The first technical enzymes were produced in the early 20th century and, not coincidentally, allergies have become the disease of our modern civilisation. The use of enzymes in industry and everyday products has increased tremendously in recent years, but remains largely unrecognised by the public and medical professionals. Food, beverage, detergent, perfume, pharmaceutical, textile and chemical industries are increasingly using enzymes in biotechnological processes for contributing to the fragrance, taste and flavour of products. The desire of consumers for natural flavours in products and aromas in low-fat foods has driven the considerable growth in this sector since the beginning of the millennium. Although the conventional routes of chemical flavour synthesis are still used, the biotechnological generation of enzymes, especially of aroma compounds, is growing.

A large variety of such enzymes are now on the market, mostly genetically modified with the help of recombinant DNA technology and expressed in different species, increasing the numbers of enzymes with potential sensitising properties into thousands.

These enzymes are suspected to be able to destroy the functions of the immune system (such as IL-2 and IgE receptors) or have a direct or indirect influence on the tight junctions ‘killer enzymes.’

Fighting against an allergy

- You can only win the fight against an allergy when you avoid the disruption of the body surface (skin and mucosae), especially the disruption of the tight junctions.

- The best way to start that fight is to avoid all industrialized products for 3 weeks, solely eat fresh vegetables, fresh fruits, potato and rice. During that time you should only drink water and fresh pressed fruit juices made by yourself.

- For allergies that involve the skin, avoid enzymes in your detergents and avoid using softener.

Killer enzymes that are found in many everyday products:

- Flour products

- Milk and dairy product

- Meat and fish products

- Industrial fruit juices and beverages

- Cleaning agents, fabric softeners, and detergents

Killer enzymes can also be found in our natural environment:

- Dust mite faeces (thanks to home designs that favour mites)

- Mould spores (thanks to home designs that favour mould)

- Pollen surfaces

- Insect and animal venom (the allergens are injected just under the skin

To read more about this theory, see the book The Real Causes of Allergies by Peter Alderman and Dr. Thomas Bohner.

About the author

Thomas Bohner, Ph.D. is a founding partner of Kalixan Ltd, a Zürich based Swiss start-up company, where he is responsible for the scientific development of hypoallergenic products. He is married and a father of two boys (10 and 13 year old).

Thomas Bohner, Ph.D. is a founding partner of Kalixan Ltd, a Zürich based Swiss start-up company, where he is responsible for the scientific development of hypoallergenic products. He is married and a father of two boys (10 and 13 year old).